Distribution

Once absorbed, a drug is distributed by the bloodstream throughout the body.

- Role of Organ Perfusion

- Role of Plasma Conscentration

- Role of Drug Solubity

- Role of Free Constitutent

The rate of rise in drug concentration in an organ is determined by that organ’s perfusion

Highly perfused organs (the so-called vessel-rich group) receive a disproportionate fraction of the cardiac output (Table).

These tissues receive a disproportionate amount of drug in the first minutes following drug administration. These tissues approach equilibration with the plasma concentration more rapidly than less well-perfused tissues because of the differences in blood flow. However, less well-perfused tissues such as fat and skin may have an enormous capacity to absorb lipophilic drugs, resulting in a large reservoir of drug following long infusions or larger doses.

Tissue group composition, relative body mass, and percentage of cardiac output.

| Tissue Group | Composition | Body Mass (%) | Cardiac Output (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel-rich | Brain, heart, liver, kidney, endocrine glands | 10 | 75 |

| Muscle | Muscle, skin | 50 | 19 |

| Fat | Fat | 20 | 6 |

| Vessel-poor | Bone, ligament, cartilage | 20 | 0 |

When the plasma concentration exceeds the concentration in tissue, the drug moves from the plasma into tissue. When the plasma concentration is less than the tissue concentration, the drug moves from the tissue back to plasma. This is the law of mass action as followed by drug molecules..

The equilibrium concentration in an organ relative to blood depends also on the relative solubility of the drug in the organ relative to blood unless the organ is capable of metabolizing the drug.

Lipophilic molecules can readily transfer between the blood and organs.

Charged molecules are able to pass in small quantities into most organs. However, the blood–brain barrier is a special case. Permeation of the central nervous system by ionized drugs is limited by pericapillary glial cells and endothelial cell tight junctions. Most drugs that readily cross the blood–brain barrier (eg, lipophilic drugs like hypnotics and opioids) are avidly taken up in body fat.

Molecules in blood are either free or bound to blood constituents such as plasma proteins and lipids. The free concentration equilibrates between organs and tissues. The equilibration between bound and unbound molecules is instantaneous. As unbound molecules of drug diffuse into tissue, they are instantly replaced by previously bound molecules. Plasma protein binding does not affect the rate of transfer directly, but it does affect the relative solubility of the drug in blood and tissue. When a drug is highly bound in blood, a much larger dose will be required to achieve the same systemic effect. If the drug is highly bound in tissues and unbound in plasma, the relative solubility favors drug transfer into tissue. Put another way, a drug that is highly bound in tissue but not in blood will have a very large free drug concentration gradient driving drug into the tissue. Conversely, if the drug is highly protein bound in plasma and has few binding sites in the tissue, transfer of a small amount of drug may be enough to bring the free drug concentration into equilibrium between blood and tissue. Thus, high levels of binding in blood relative to tissues will increase the rate of onset of drug effect because fewer molecules will need to transfer into the tissue to produce an effective free drug concentration.

Albumin has two main binding sites with an affinity for many acidic and neutral drugs (including diazepam). Highly bound drugs (eg, warfarin) can be displaced by other drugs competing for the same binding site (eg, indocyanine green or ethacrynic acid) with dangerous consequences. α1-Acid glycoprotein (AAG) binds basic drugs (local anesthetics, tricyclic antidepressants). If the concentrations of these proteins are diminished, the relative solubility of the drugs in blood is decreased, increasing tissue uptake. Kidney disease, liver disease, chronic heart failure, and some malignancies decrease albumin production. Major burns of more than 20% of body surface area lead to albumin loss. Trauma (including surgery), infection, myocardial infarction, and chronic pain increase AAG levels. Pregnancy is associated with reduced AAG concentrations. None of these factors has much relevance to propofol, which is administered with its own binding molecules (the lipid in the emulsion).

The complex process of drug distribution into and out of tissues is one reason that half-lives provide almost no guidance for predicting emergence times. The offset of a drug’s clinical actions is best predicted by computer models using the context-sensitive half-time or decrement time. The context-sensitive half-time is the time required for a 50% decrease in plasma drug concentration to occur following a pseudo-steady-state infusion (in other words, an infusion that has continued long enough to yield nearly steady-state concentrations). Here, the “context” is the duration of the infusion, which defines the total mass of drug remaining within the subject. The context-sensitive decrement time is a more generalized concept referring to any clinically relevant decreased concentration in any tissue, particularly the brain or effect site.

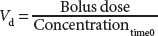

The volume of distribution, Vd, is the apparent volume into which a drug has “distributed” (ie, mixed). This volume is calculated by dividing a bolus dose of drug by the plasma concentration at time 0. In practice, the concentration used to define the Vd is often obtained by extrapolating subsequent concentrations back to “0 time” when the drug was injected (this assumes immediate and complete mixing), as follows:

The concept of a single Vd does not apply to any intravenous drugs used in anesthesia. All intravenous anesthetic drugs are better modeled with at least two compartments: a central compartment and a peripheral compartment. The behavior of many of these drugs is more precisely described using three compartments: a central compartment, a rapidly equilibrating peripheral compartment, and a slowly equilibrating peripheral compartment. The central compartment may be thought of as including the blood and any ultra-rapidly equilibrating tissues such as the lungs. The peripheral compartment is composed of the other body tissues. For drugs with two peripheral compartments, the rapidly equilibrating compartment comprises the organs and muscles, while the slowly equilibrating compartment roughly represents the distribution of the drug into fat and skin. These compartments are designated V1 (central), V2 (rapid distribution), and V3 (slow distribution). The volume of distribution at steady state, Vdss is the algebraic sum of these compartment volumes. V1 is calculated by the above equation showing the relationship between volume, dose, and concentration. The other volumes are calculated through pharmacokinetic modeling.

A small Vdss implies that the drug has high aqueous solubility and will remain largely within the intravascular space. For example, the Vdss of vecuronium is about 200 mL/kg in adult men and about 160 mL/kg in adult women, indicating that vecuronium is mostly present in body water, with little distribution into fat. However, the typical general anesthetics is lipophilic, resulting in a Vdss that exceeds total body water (approximately 600 mL/kg in adult males). For example, the Vdss for fentanyl is about 350 L in adults, and the Vdss for propofol may exceed 5000 L. Vdss does not represent a real volume but rather reflects the volume into which the administered drug dose would need to distribute to account for the observed plasma concentration.

Reference

1. Pharmacological Principles. In: Butterworth IV JF, Mackey DC, Wasnick JD. eds. Morgan & Mikhail’s Clinical Anesthesiology, 7e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2022. Accessed December 23, 2025. https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3194§ionid=266517902